A Case for Both Cases in the Classroom

“He who knows only his own side of the case knows little of that. His reasons may be good, and no one may have been able to refute them. But if he is equally unable to refute the reasons on the opposite side, if he does not so much as know what they are, he has no ground for preferring either opinion...”

I begin every course I teach with this quote from John Stuart Mill. This is one of three ethos in my classes: to understand both sides of an argument before you form yours.

The highly connected world makes it almost an impossibility for young people to be a blank slate when entering the classroom — everyone from the news anchors their families watch to the Instagram-famous promoting their political leanings — but I nevertheless ask students to approach each subject with an open mind. This does not mean refraining from having an opinion; rather, it suggests taking apart those opinions often given to us and recreating them with better knowledge, evidence and even divergent viewpoints.

A successful classroom aims to encourage individuality and autonomy over one’s learning, and this cannot exist without Mill’s assertion. So, educator, parent or really any thinking human, here’s why a commitment to teaching both sides of an argument produces better students and participants in our world.

The Importance of Evidence

“You can have any opinion you want, but you have to support it with evidence.” I say this almost every class. Encouraging students to explore both sides of an argument forces them to critically examine the evidence. Moreover, it paradoxically teaches students

How to support your argument in the face of conflicting evidence

The self-reflection and humility to change your argument in the face of conflicting evidence

With either outcome, you produce critical thinkers and the capability to cope with resistance or one’s wrongness. The classroom offers students a space to explore controversial topics, to expand boundaries set in their minds, and the “right” and “wrongs” given to us without question.

Good and bad ideas are everywhere; the only thing that truly sets them apart is the ability to present hard evidence. Repeating talking points is not evidence, nor does it demonstrate individualized critical thinking, a character trait that will repeatedly be valued as a student starts to enter into adulthood and the world stage. Hard evidence stands on its own. It must be respected, encouraged and sought after within the education system.

Images from William Saville-Kent's The Great Barrier Reef of Australia (1893). Source: https://www.rawpixel.com/board/414407/great-barrier-reef-australia?sort=curated&rating_filter=all&mode=shop&page=1

2. Understanding

This may seem obvious, but it is possibly the least recognized: When a student learns the reasoning from both sides of an argument, it forces them to see those with opposing viewpoints less as opponents and more as people. This prevents writing someone off with a swift, “Well they’re just crazy” or “It’s just because they’re X”. Exposing students to multiple viewpoints, even unpopular or controversial ones, stimulates the ability to have thoughtful and intelligent discussions, rather than reacting with ignorant dismissal or emotional outbursts.

Furthermore, understanding both sides leads to a host of other benefits aside from connecting with the person on the other side of the argument. It promotes dialogue rather than dismissal, rational reactions rather than emotional outbursts, and the challenge to articulate a position rather than regurgitating regular talking points.

Examining the complexities of an issue leads to better understanding between people, and, moreover, the ability to engage in discussion. Essentially, it promotes true understanding of the subject.

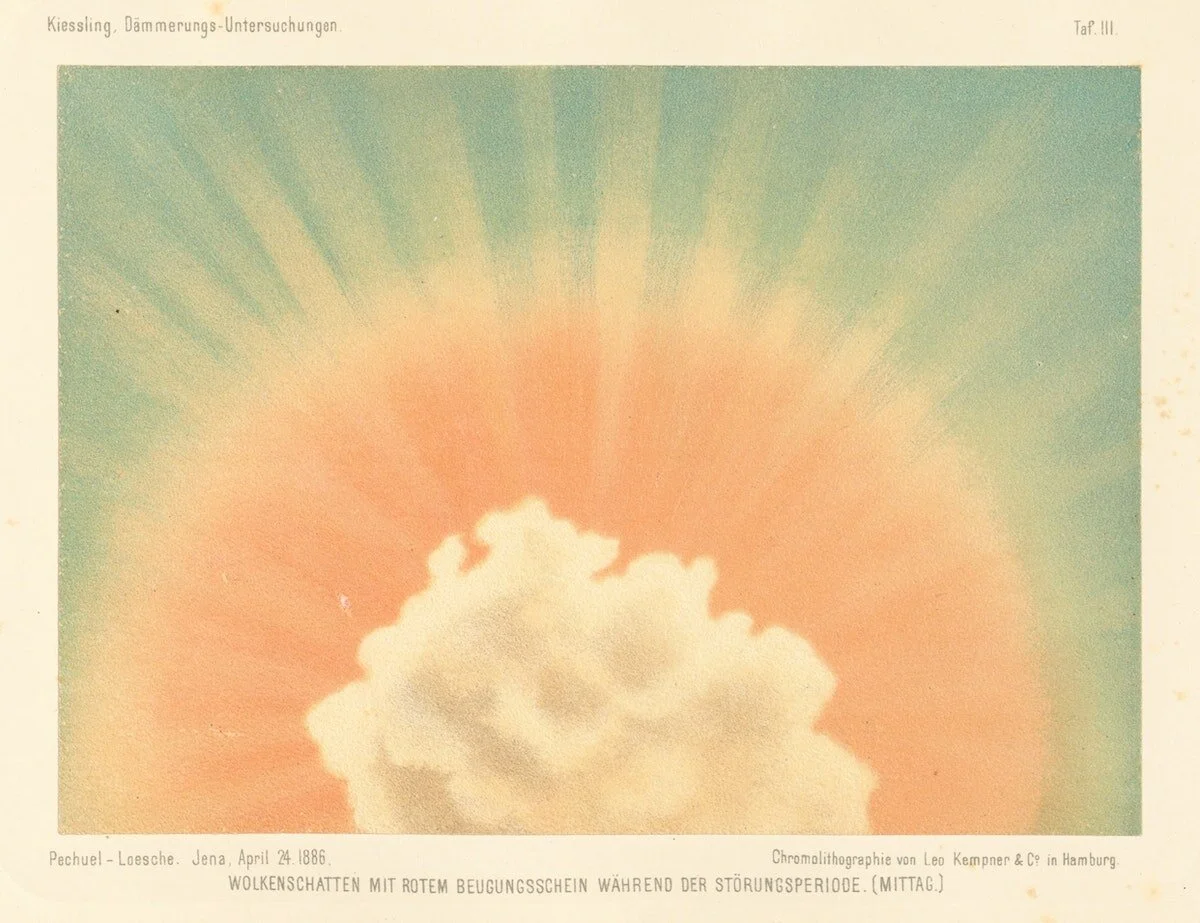

Studies on Twilight Phenomena, after Krakatoa (1888). Source: https://doi.org/10.3931/e-rara-56381

3. The Challenge and the Common Sense

In the end, Mill sets up a personal challenge for each of us: Question your beliefs.

This is the opportunity that the classroom provides, giving students the space to raise questions and challenge narratives. 15 percent of the average American life is spent at school - this is not insignificant. This is the time for students to explore who they are, what they believe and come to their own conclusions, not decisions imparted by me, their parents, other teachers, the news or what they read on social media. They need this space. They need the opportunity to engage with a plethora of opinions; perspectives that, through engaging with them, will create better thinkers and give them autonomy over their lives and learning.

East of the Sun and West of the Moon, illustrated by Kay Nielsen (1922 edition). Source: https://archive.org/details/eastofsunwestofm00asbj/page/n7